Volcanism in Italy

An initial overview of volcanoes

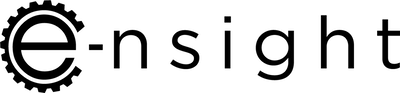

Italy and the Mediterranean Sea contain some of the most important volcanic sites in the world, known for the scientific and historical interest that they spark. Fate had it that Italy is entirely stuck between the Eurasian and the African tectonic plate. The simultaneous thrust of one against the other caused the formation of our mountain ranges and several volcanoes, that are mostly situated in southern Italy.

Map of the interactions between the Eurasian and the African plate.

Those who live in Italy have the problem of living close to a volcano to heart, especially those who live in Campania, Sicily or Eolian islands. The Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV) is in charge of monitoring and studying all the volcanic and seismic phenomena in Italy and in the world. The Istituto collects data on volcanic phenomena, draws up the guidelines in case of evacuations and ensures the habitability of the areas situated in immediate proximity to volcanoes. If anyone who is reading this lives or has lived nearby a volcano, they surely know that Italian volcanoes are not exactly friendly. However, each one of them offers research opportunities that are unparalleled in the world.

A volcano for a friend, or almost…

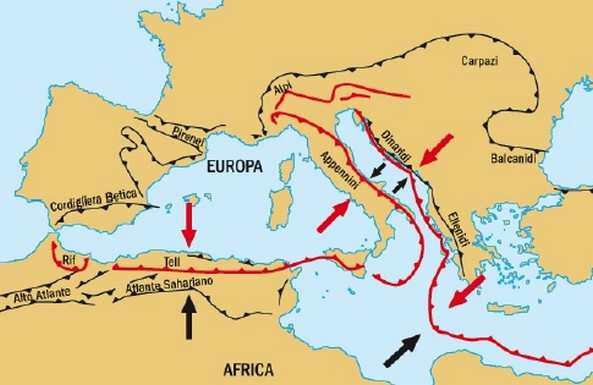

Mount Etna, situated in Eastern Sicily, is long since known as the “gentle giant“. Its formation dates back to 100.000 years ago, when magmatic material began pouring out of the hotspot that is still feeding the mountain to this day. The volcano itself is not known in particular for disturbing human life but, according to shared memories of inhabitants of the Etnean territory, “a Muntagna si fa sìentiri” (from the dialect: “the mountain makes itself heard”). The surrounding area is indeed interested by minor periodical seisms, whilst quakes of great magnitude are rare.

We remember the recent seism of December 26th 2018 that hit Milo and the nearby villages with an earthquake swarm whose peak was 4.8 on the Richter scale and hypocenter at 1 km.

Extension of Mount Etna, and nearby Etnean villages.

The activity of Mount Etna fluctuates between explosive and effusive, because of the variable viscosity of the lava. When the magma is more viscous, in fact, it doesn’t allow the gases to escape easily. This causes an increase in the average pressure inside the caldera and provokes the typical thunderous explosion, with production of ashes and lapilli. On the contrary, the effusion of slightly viscous lava represents a lesser problem. This type of lava, in fact, does not trap gas bubbles, not causing pressure increases in magma volumes. The alternation of fluid eruptions and explosions has defined the ambivalent nature of shield volcano and stratovolcano. The eruptions of Mount Etna are famous for the plumes of bright red lava, that stand out with stark contrast to the dark of night.

Effusive eruption of Mount Etna

Etna may look like a “gentle” volcano because of its constant activity, but we must not forget about the fact that it still is a volcano. Its most famous eruption, dating from 1669, destroyed the city of Catania and expelled almost a billion cubic meters of lavic material. Below you will find an accurate reconstruction of the 1669 lava flow, from which we can clearly recognize an addition of lavic material to the Catanian coast.

Pressure cooker!

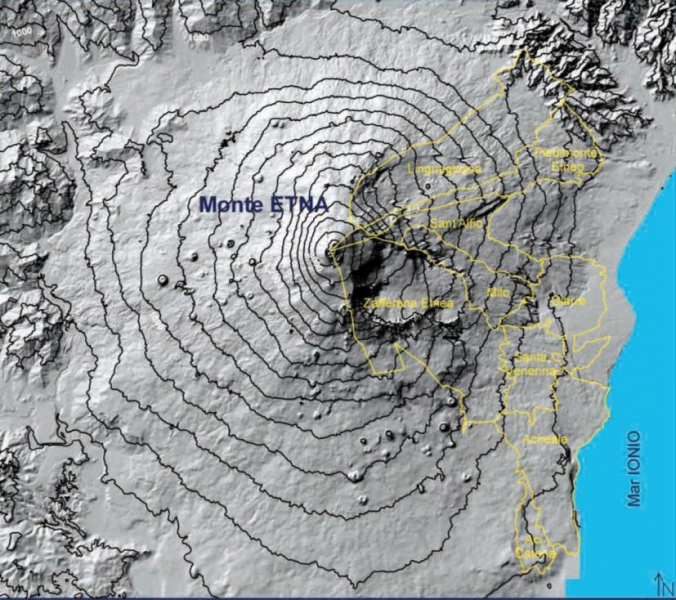

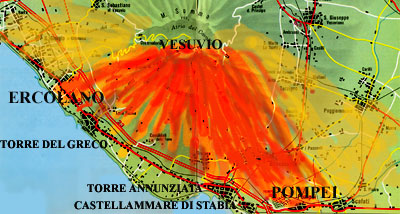

The area of Campi Flegrei and the vulcanic complex Somma-Vesuvio are situated near the south-eastern metropolitan area of Naples. The Vesuvius is the survivor of an ancient volcanic system deflagrated during the historic explosion of 79 AD, that destroyed Ercolano, Pompei and Stabia. Since 1944, year of the last eruption of Mount Vesuvium, there has been detection of only minor seismic activity and frequent gas emissions from fumaroles.

Reconstruction of the ancient complex Somma-Vesuvio

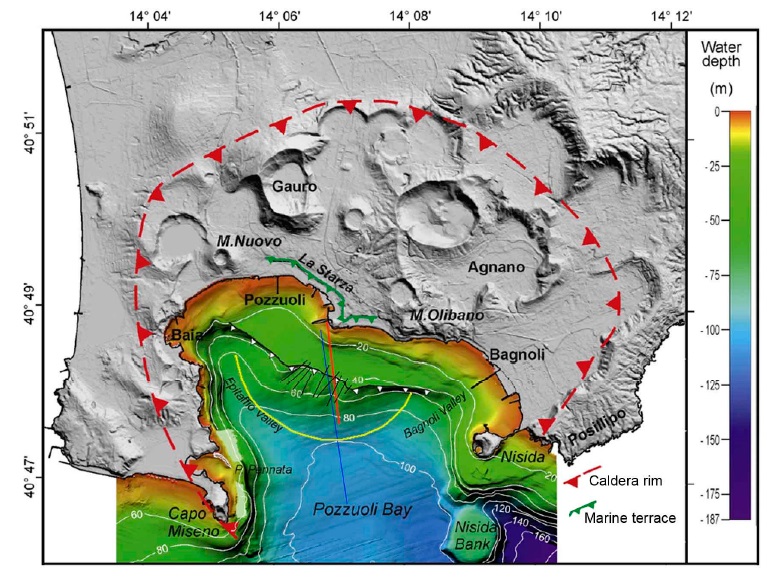

The site of the Campi Flegrei sparks a particular interest because of the frequent phenomenon of bradyseism to which it is subject. In a few words, in a location subject to bradyseism the level of the goes up and down, due to the movement of large masses of magma below the interested area. Therefore, an interdependent action between subterranean magmatic flows and local seisms is by no means to be underestimated. An evident example is given by the seism of Pompei of February 5th 62 AD. For a long time it has been assumed that this seismic event, described by Lucio Anneo Seneca in the sixth book of the Naturales quaestiones, could have been connected with the 79 AD explosion because of their temporal proximity. Unfortunately this hypothesis can not be confirmed.

Infographic of the eruption in the Roman era that destroyed Pompei, Ercolano, Stabia and Oplontis.

Everything may seem under control, but a dormant volcano turns out to be much less predictable than an active volcano. Two eruption of the same volcano have a rest period in between, which normally provides an indication of the periods of activity of the volcano itself. When the eruptions don’t occur according to these estimated periods there is fear for a more violent eruption, due to both the pressure increase on the walls of the caldera and possible seisms connected with the increased force of the eruptive activity.

Overview of the extension of the Campi Flegrei caldera.

Submarine volcanoes

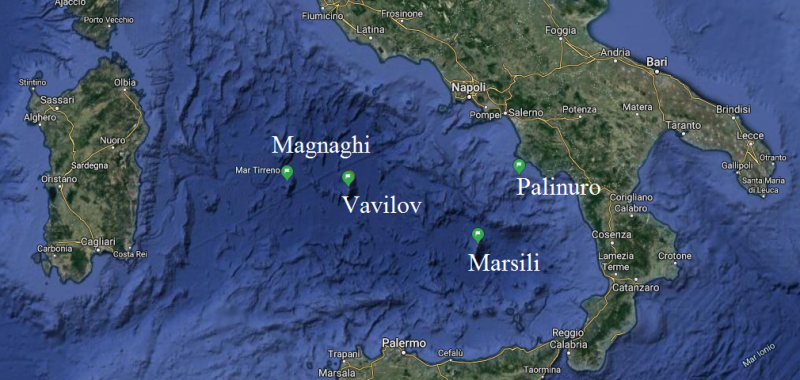

Etna and Vesuvio are not the only volcanic sited monitored by the INGV. Actually, the Tyrrhenian Sea and the Strait of Sicily hide several underwater volcanoes, that are morphologically different from above-ground volcanoes. Many of them, in fact, appear as mid-ocean ridges, formed near the thinnest spots of the earth’s crust.

Screenshot from Google Maps depicting the position of submarine volcanoes in the Tyrrhenian sea.

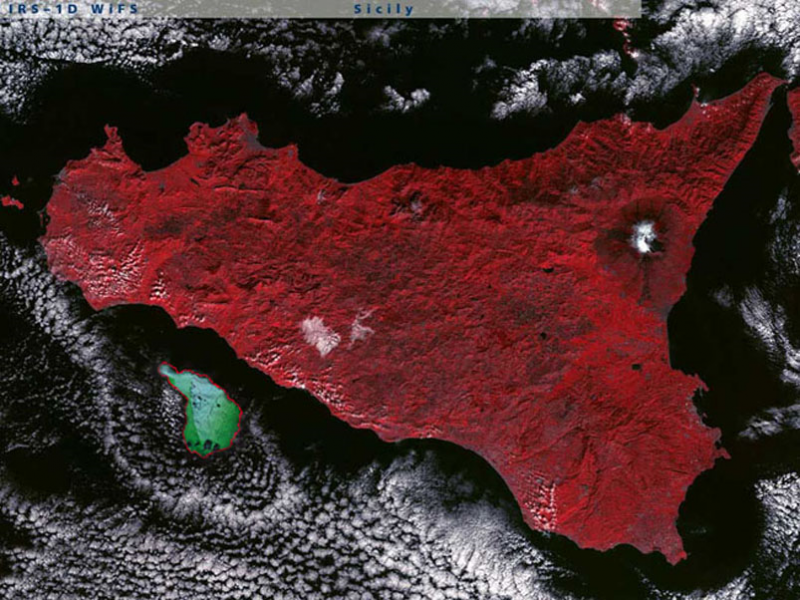

Their activity mostly consists of the emission of gases and rock material that fall back down on the seabed. They may look like harmless activities, but the movement of magma beneath the crust suggests a far more dynamic activity. Marsili, Palinuro and Magnaghi are the active volcanoes of Tyrrhenian Sea, whilst the Terribile, the Empedocle and the Ferdinandea are situated in the Strait of Sicily.

Satellite picture of the submarine volcano Empedocle (in green)

It is interesting to notice the distribution of the various volcanic mouths in the Tyrrhenian site. The concentration of submarine craters north of the Sicilian coast, suggests that, in a near future, we may witness the birth of new volcanic islands, besides the already known island of the Aeolic archipelago, namely Stromboli and Vulcano.

Secondary volcanism

On Italian territory are located many sites that are subject to phenomena of “secondary volcanism”. Its vast definition includes any interaction between magma and soil, rising gases and aquifers.

Material manifestations of these interactions are geysers, fumaroles, solfatare, thermal springs, mud and clay cones and mofette. The best known sites are the solfatare of Pozzuoli, the Salinelle of Paternò, the Salse of Nirano, the fumaroles of Campi Flegrei and Larderello, the thermal springs of Saturnia and the mofete in Irpinia.

Localization of the various primary and secundary volcanic phenomena in Italy.

Many of these phenomena, in particular solfatare, produce a considerable quantity of energy, that can be exploited for several uses. In another article, to which we refer you with this link, you will discover how the extraction of geothermal energy from sites that are subject to secundary volcanism phenomena is fundamental for many industrial processes and for the heating of domestic environments

.

Mud cone in the site Salse of Nirano, in the province of Modena.

Graphic sources

- Protezione Civile

- Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia

- Luca Nacchio (Flickr) (mud cone picture)

- SkyTG24 (satellite picture of the volcano Empedocle)

- L’Astrolabio – Amici della Terra(map of the volcanic phenomena in Italy)

- MeteoVesuvio (Caldera of Campi Flegrei)

- ResearchGate(map of the tectonic plates)

- Live UniCT(eruption of Mount Etna)

- PassioneEtna(reconstruction of the 1669 eruption of Mount Etna)